Judie Johnson – Turning Points in Nature

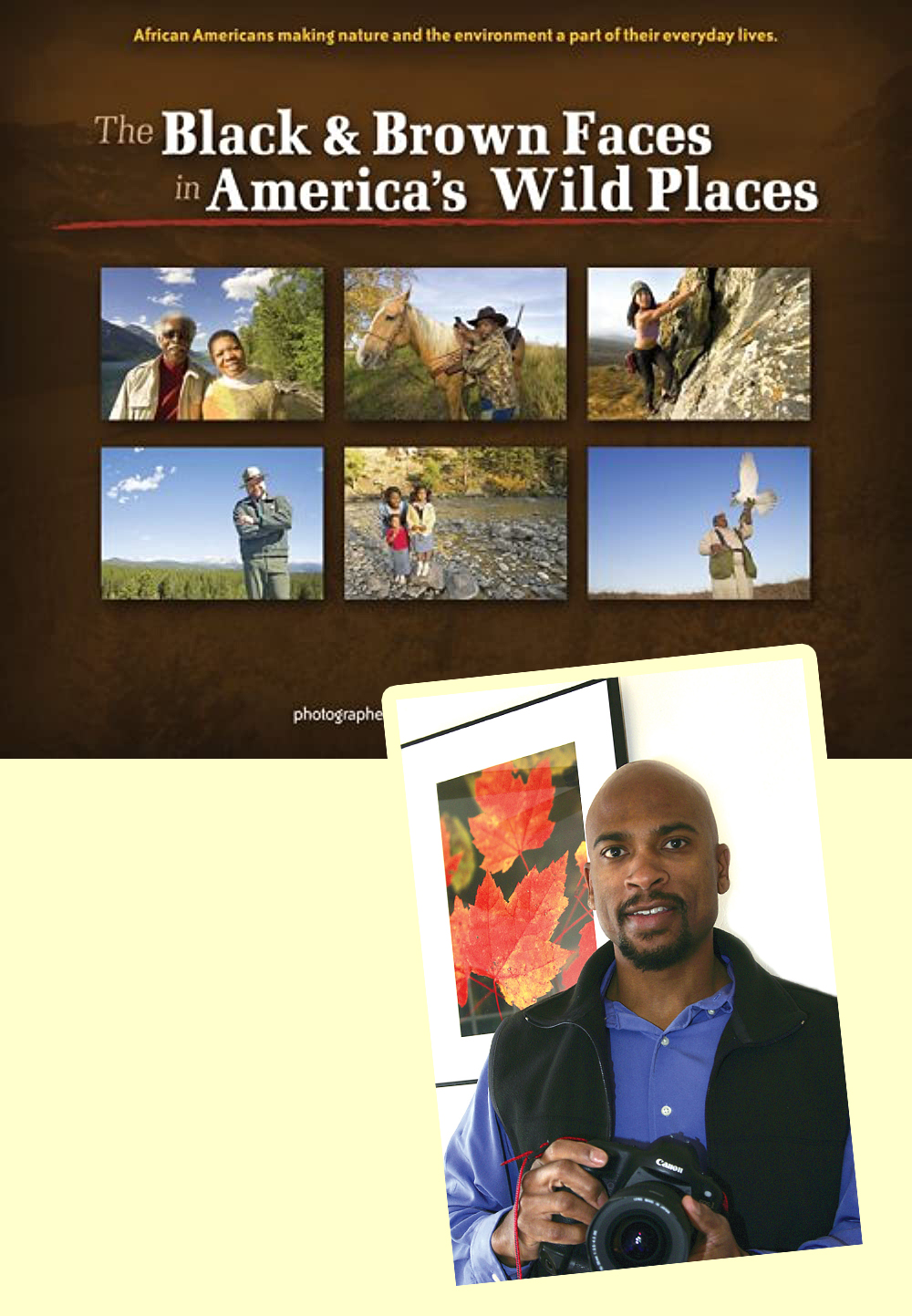

In 2006 Dudley Edmundson conducted a series of interviews with African American outdoors-people that culminated in the book Black & Brown Faces in America’s Wild Places.

A lot has changed, in the world, and around the United States, in the 17 years since Black & Brown Faces in America’s Wild Places was first published. Yet, when reading through the interviews, it is easy to see the common themes and energy that link all of their experiences with the growing outdoor community who LOOK like them and share their passion for nature and the outdoors.

Over the coming months we will be sharing the interviews from Black & Brown Faces in America’s Wild Places here on our blog, and we hope you can find your voice to add to those celebrating their passion for the outdoors.

The following excerpt is taken from an interview with Judie Johnson back in the early 2000’s when she was the Executive Director, Gunflint Trail Association.

I am the Executive Director of the Gunflint Trail Association in northeastern Minnesota. The Gunflint is a vacation destination for people from around the region and the world. The 57-mile paved highway goes north out of Grand Marais, Minnesota, through some of the most beautiful wilderness areas you may ever see, and turns west, ending on Saganaga Lake near the Canadian border. People visit the trail to access the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. There is so much to do off the Gunflint at any time of the year, including fishing, camping and hiking and skiing in the winter. You can watch wildlife at all times of the year. Moose, bears, wolves, deer and a host of other cool animals make the area their home. The best part about my job is telling tourists how to have fun in a place that I love.

By most people’s standards, Grand Marais would seem very remote. Most of what we do here is outdoors. Closest movie theater or shopping mall is 75 miles away. I tell people, “There is Lake Superior, it’s right there in front of you. It is the largest freshwater lake in the world, and you can’t find anything to do?”

Childhood Experiences and Turning Points in Nature

As a child growing up in Chicago, Illinois, in the Lake Meadows area, I got to experience a lot of Chicago’s Lake Michigan waterfront and some of the parks there.

My father’s parents lived on a farm near Alton, Illinois, close to St. Louis, until their deaths, so we were at the farm quite a bit. My father and my grandfather and uncles would be on tractors, so I would be out there watching them work or following them around. It was a working farm—cows, chickens, horses and pigs. They raised most of their food. We got to do all those living-off-the-land things that most kids don’t get to do. The area where my grandparents farm was and is still a little wild, but with urban sprawl I think it will all be gone in a decade or so, which is kind of sad.

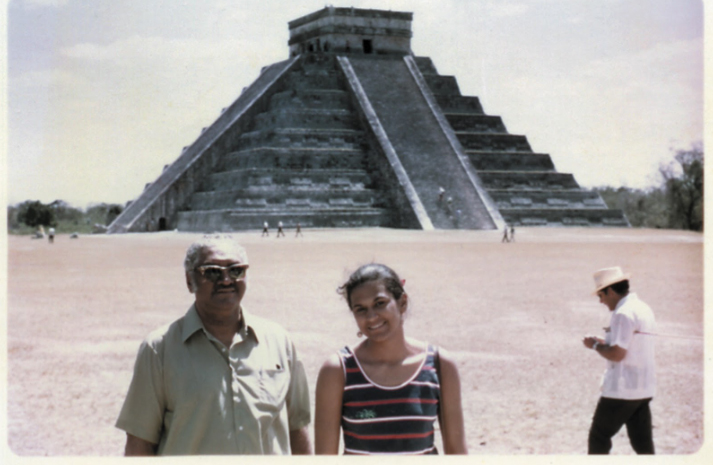

Our family took vacations a lot during my childhood, which a lot of blacks did not get to do back then. We would go for two to three weeks. We would camp and stay in hotels. My sister and I read National Geographic, so we would plan vacations using information in them. We traveled all over. We were a curious family, wanting to see things we had never seen before—my parents nurtured that.

One year we took a trip from Chicago across the country to Yellowstone National Park, the Painted Desert, Mesa Verde National Park and a few other places. We visited my father’s brother and my mother’s aunt in L.A. Then we went up the coast and camped at Big Sur. Then we went to the Hearst Castle of W. Randolph Hearst, the millionaire, in San Simeon. There was a black guy there who was a tour guide and he gave us a private tour, so that was pretty cool. After that we went up to San Francisco. From there we stopped at Yellowstone, the Tetons, then through the Badlands of the Dakotas, eventually making our way back to Chicago. We stayed at a lot of national parks and some state parks.

On another trip we visited Lake Louise in Jasper, Canada, then went out on the Athabaska Glacier. I was so excited that my heart was going a mile a minute when we got out of the snow tracker, the vehicle that they take you out on the glacier in. They told us all about the formation of the glacier. As the guide was talking, I could see over in the distance there was a group of people. So I told my father, “Let’s go see who they are.” So we went over, and I was pleased to find out it was none other than a National Geographic magazine crew out working on an upcoming project. So I, of course, was extremely excited, to say the least. I got to talk with them and find out what they did and why they were over there. They sent me a special reprint of that copy of the magazine, which was really cool.

What I Do in the Outdoors

I actually bought land here, knowing that some day I wanted to move here. One day I was sitting at home in Minneapolis trolling their local paper and there was the Gunflint Trail Association director job. I thought to myself, “OK, by the time I am ready to move up there, something like this is bound to come up open again.” So my sister called me on the last day they were accepting applications for that job and said, “If you don’t apply, I will get an old copy of your resume and send it in.” I said, “OK, fine,” and I faxed in a current version of my resume to the office. I got a call within a few hours of sending the fax. Long story short, they made me an offer. So I accepted the job.

I remembered my mother telling me that when I was 10 years old I returned from a summer camp in Wisconsin and announced that I was moving to the woods when I grew up. So when I moved up here to Grand Marais, it was no shock to her. I am pretty sure I am the only black woman living in the whole town. People asked my mom, “What is wrong with Judie?” And she told them, “Judie told me she was moving to the woods a long time ago, and now she has finally done it.”